/Alex p.To: presentzine@yahoo.com

Date: Fri, 30 Apr 2004 20:24:07 -0400

Dear Present,

Reverend Billy was arrested on 56th and 5th after he resisted a gang of policemen who started shoving him, and his old-fashioned cheerleader bullhorn, out of the Disney Store. He had led us in there with the zeal of a fervent multinational CEO conquering a ripe market, except this is exactly what he isn't. A wavy mane of blonde hair on top of a white suit and a pair of black sneaks that can't stop bouncing, he had already attracted a crowd in front of the Equestrian statue near the Plaza with his anti-consumerist entreaties. "Brothers and Sisters, We Will not go into STARBUCKS to buy a LA-TTE! What happens to your money when you hand it over to them? You cannot TRACK it! It goes to the pockets of Howard Schultz! It goes to Ariel Sharon! It stays far away from the hands of the coffee pickers of the Nicaraguas, of the South Americas! Can I get a WIT-ness!" Cheers, shouts of “A-MEN!” Next, fifty of us, the (wonderfully festive and harmonic) Stop Shopping Choir, and about the same number of policemen marched behind Billy as he led us across the street to FAO Schwartz, where he declaimed against "WAR TOYS!" Part political and social activists, part revelatory circus of performance art, the parish continued its procession past the overweight shoppers with bags dangling and mouths ajar, delivering the Good News to them as we passed. By the time I was standing outside of the Coca Cola building, listening to another preacher describe the "killer" practices of that company in its manufacturing and union-busting (this part was made less clear by lack of a bull-horn, and the din of traffic and shopping bag covered onlookers), I realized an eager tourist behind me was aiming his camcorder right at my mug. But this was not your average Midwestern gawker: upon closer inspection, he had an NYPD pin affixed to his jacket. Suddenly I felt daring, like a shirtless spring breaker in front of MTV producers: I put on my most concerned-looking face and delivered my own on-camera plea to "put down that camera, and live your own, real life!" Nevertheless, this surveillance persisted in the Disney Store by other "tourists"; there was much to capture. As the Reverened pulled out his megaphone near a large display of stuffed animals and shirts to proclaim the fact that "Your children wear these clothes--Other children make these clothes!", cops began to shove some of the assembled out of the store, their hands twitching over plastic cuffsand pepper spray holsters. It was understandable in some ways, but it was also infuriating: a policeman I and another fellow spoke with afterwards could give no explanation for Billy's arrest, though he did suggest that he had committed a crime of some sort. One charge I heard was "blocking the sidewalk".

As some of us later stood on the corner of 55th and 5th, a heavy-set man with a small face and a trench coat fixed his digital camera on our group. There was no badge but there was also no mistaking this man's familiarity with the words "perp" and "stake-out." Tell me, is anti-consumerist, anti-supercorporate activism really a threat in this day of international terrorism? Or perhaps the better question is, is there any longer a difference between a group of terrorists armed with guns and knives trying to destroy a government and a group of concerned people armed with flyers and songs hoping to make fun of (and, god, have fun, at the expense of) multinational corporations? Perhaps there’s not much of a difference so long as consumerism means being American, “free” speech refers more to dollars than to liberties, and every day our government looks a lot more like one of those big name-brand corporations

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Can't Buy Me

Thursday, November 23, 2006

Blogspot is Back in China

It never made sense to me that China would block blogspot without blocking the dozens of other blogging sites. Perhaps it had something to do with blogspot owner Google's unwillingness to play ball with government censors as yahoo had done in notoriously releasing the name of a blogger to the government; but has Google's policy changed?

In fact, that's the worst thing about the censorship: we don't know. The censorship is so random, and it's so hard to know what will be censored, or why or when, that it feels almost calculated to be random. That of course creates the sense that the government has a wide r reach than it really does, and generally messes with your head. You'll never know what site will be blocked, because the government's always on the move, always got its eyes out.

It's the internet version of Foucault's panopticon: power all-visible yet always unverifyable.

... the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power. So to arrange things that the surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action; that the perfection of power should tend to render its actual exercise unnecessary; that this architectural apparatus should be a machine for creating and sustaining a power relation independent of the person who exercises it; in short, that the inmates should be caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers. To achieve this, it is at once too much and too little that the prisoner should be constantly observed by an inspector: too little, for what matters is that he knows himself to be observed; too much, because he has no need in fact of being so. In view of this, Bentham laid down the principle that power should be visible and unverifiable. Visible: the inmate will constantly have before his eyes the tall outline of the central tower from which he is spied upon. Unverifiable: the inmate must never know whether he is being looked at at any one moment; but he must be sure that he may always be so. In order to make the presence or absence of the inspector unverifiable, so that the prisoners, in their cells, cannot even see a shadow, Bentham envisaged not only venetian blinds on the windows of the central observation hall, but, on the inside, partitions that intersected the hall at right angles and, in order to pass from one quarter to the other, not doors but zig-zag openings; for the slightest noise, a gleam of light, a brightness in a half-opened door would betray the presence of the guardian. The Panopticon is a machine for dissociating the see/being seen dyad: in the peripheric ring, one is totally seen, without ever seeing; in the central tower, one sees everything without ever being seen.

(Also see Rebecca MacKinnon's good post on human rights and the Great Firewall.)

Towering Ambitions

by Alex Pasternack

Important architects tend to look and sound as ostentatious as their designs, which is why you may not immediately recognize Ole Scheeren. The angular 35-year old German was sitting in a coffee shop in the Central Business District recently, wearing a shirt with an open collar, a pair of jeans, a day-old beard on his schoolboy face, and none of those self-consciously eccentric glasses by which architects are sometimes known. Discussing his latest project, his speech was unassuming, thoughtful, and curious; he even arrived early. He hardly seemed, in other words, like the lead designer behind the

“If you would preoccupy yourself with feeling so great about what you’re doing, there is an implicit loss of criticality vis a vis what you’re doing,” he says in his light, clean European accent about CCTV going to his head. “And in the case of this project it would be a fairly fatal to the momentum. It requires total attention at every point at time. There’s very little time to think about it.”

Nor does the project give Scheeren much use for the sort of rhetorical flourishes for which architects, like his famous Dutch mentor and co-architect on the project, Rem Koolhaas, are sometimes known. And when Scheeren does say things like “this may be the most complex building ever built,” he’s not kidding.

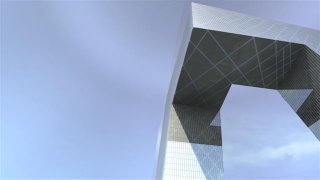

Since it was approved in an orgiastic moment of development in 2002, the 450,000 square-meter glass and steel China Central Television headquarters literally twists the conventional skyscraper into a gravity-defying three-dimensional trapezoid in the impossible style of M.C. Escher. Nearby sits a companion building, the public-oriented Television Cultural Center (TVCC), which resembles a cubist boot. They’re a feat of architectural gymnastics (and careful diplomacy) that has left many confused, worried, or downright disbelieving. One might just be just as incredulous about the architect’s age.

“Being 35, in a lot of professions, you’re a grandfather already, but in architecture you’re seen as being young,” he says. Raised by an architect-father, and harboring building aspirations early on, “in a way I have the feeling that I started quite early, so I don’t feel quite that young anymore.” But, how prepared could he be to manage a team that at one point exceeded 400 architects and engineers? When I marveled aloud that this project would be the biggest, in terms of scale, that he or OMA had even built (his last project was a triplet of Prada stores in

Scheeren isn't worried about his relative lack of experience. “First, you have to ask what type of experience is relevant to run a project like this. It’s a project that exceeds the scale of anything done so far, and so experience is not valid in the traditional sense,” he says, without a note of pretension. “And it takes an enormous energy that you can hardly generate in your 60s,” an age group that Koolhaas recently reached.

Scheeren isn't worried about his relative lack of experience. “First, you have to ask what type of experience is relevant to run a project like this. It’s a project that exceeds the scale of anything done so far, and so experience is not valid in the traditional sense,” he says, without a note of pretension. “And it takes an enormous energy that you can hardly generate in your 60s,” an age group that Koolhaas recently reached.

“The point is to say you don’t know how it works, and don’t know how the context works, and to develop a structure that allows change within the process.” It turns out that that sort of radical thinking informed the design all along, from its hastily-imagined loop to the lattice external steelwork that supports the building. But such uncertainty—and at such cost, with an initial reported budget of $700 million—didn’t sit well with either critics or the authorities. A year after a contract was signed, the government ordered a review of all new buildings, and (so rumor went) the television building was to be taken off the air. For one and a half years, the CCTV construction site sat untouched. When the cranes rose again, following a rigorous official review, the budget had reportedly grown to $1.2 billion. But Scheeren wasn't fazed.

“The thing is, we never stopped working on the project,” Scheeren says. Continuing work in

But Scheeren also acknowledges that such a daring design could not have been undertaken anywhere but in

To be sure, the CCTV project—with its radical shape, recreation areas named the “fun belt” and the “fun palace,” and a section specially designed for visitors—seems an unlikely undertaking for one of the world’s largest propaganda machines, and a government famous for concealment. This (disturbing) irony hasn’t gone lost on Scheeren. Indeed, he practically revels in it.

“[Building] CCTV was seen from the beginning as a tool for change from inside the company,” he says, alluding to a cadre of risk-taking “younger people leading CCTV, lying beneath the skin of the older generation,” who championed the design. When he talked about the building recently at an exhibition in its honor that he curated at the Courtyard Gallery and soon to move to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Scheeren practically avoided discussing the design, focusing instead on what the building’s open layout might mean to the everyday Beijinger, and for a 21st century China. “It’s a change that exists beyond the realm of architecture. I’ve always been interested in that.”

Indeed, dramatic change and breadth have been the motif of Scheeren’s work as much as his life. It was an early introduction to the profession through his architect-father and his first commission at age 21 that initially burned him out. For a while, playing rock music seemed more appealing. “You’re so close to it, it’s uncomfortable,” he says of his architecture pedigree. Things changed when he heard a presentation by Rem Koolhaas, whose own interests beyond architecture (he had once been

After butting heads with teachers at the design academy in his home town, the south-west German city of

“In retrospect, it’s hard to figure out how it all happened,” he says as he stares at the table, slightly smiling. “Maybe I had the feeling that I had nothing else to lose.” Koolhaas threw Scheeren onto a project that seemed on the verge of failure, with two weeks until deadline. The 18-hour days paid off, he says proudly. “It was the only competition oma had won in a year and a half.”

But the restless Scheeren left OMA almost as quickly as he had arrived, taking a graphic design gig in

When OMA bid on the CCTV project in 2002 (declining an invitation to make a proposal for Ground Zero), Scheeren made his biggest shift yet, from designing clothing boutiques to constructing one of the largest buildings in the world.

Having relocated to

Aside from not having enough time to study Chinese (“it’s the biggest frustration of being here… My plan is that before the building is finished. I need to get a whole step ahead”), Scheeren is still adapting to the process of constructing buildings in

“I think part of the role of architects coming to build here is not only to bring a different sense of design but to try to step back and urge them,” planners, developers, clients and contractors, “to open up more lines of communication.” Scheeren says he aims for slower, careful consultations when proposing projects, like his successful bid for a new Beijing Books Building and a Prada “epicenter” store in Shanghai (When we met, Scheeren said OMA’s chances to renovate the stock exchange in Shenzhen were “promising.”)

Though the

“Many people still don’t believe it’s going to happen,” Scheeren says, with some exasperation, but also a bit of delight. The truth is, neither can he.

“You think it can’t happen. And then you finally see the piles being driven into the ground, and the steel rising,” he says, with a faint smile. “These are the only moments that you believe that it is really happening.”

this article was published in that's Beijing magazine (tbjHome), August 2006

Thursday, October 19, 2006

Islands

TEA AND CAKES

Old School

2/F 17 Yun Ping Road

Causeway Bay

2983 2130

This unmarked upstairs cafe, floating above a corner of Causeway, is cool for school. Kat took us there originally, and she had been taken by some local friends of hers, who had in turn been taken by their friends. It's that sort of place, off the map, but it's also unlike any sort of place at all--except for a homeroom you never had. And with tasty cakes and things. My favorite bathroom in the shopping mall city.

BOOKS

Flow

2/F 40 Lyndhurst Terr

Central

Good used books, especially if you're headed to China for a year.

MUSIC

White Noise Records

1/F, 4 Canal Road East

Causeway Bay

Best record shop + place to sit and look at big glossy art magazines.

THINGS

Kapok

G/F. 9, Dragon Road, Tin Hau.

Tel: 254 99 2564

www.ka-pok.com

DANCE

Volar

38-44 D'Aguilar St

Lan Kwai Fong

2810 1510

If I have to tell you... Better make sure you're a model, preferably from Ukraine or Finland, or tell the bouncer your name is Ilya or Austin.

ISLAND

Lamma

Island

No woman is an island.

Saturday, August 12, 2006

The For-Building City

While in Hong Kong—which is just China's most recent (re)acquisition, but can feel like London or NY—I read of a red dragon that was changing, feeling the pressure that comes with 9 percent year on year economic growth, and the pressure that comes with thousands, millions of people who are losing their homes and farmlands to the factories and dams meant to sustain that growth. I heard and saw a bit of how

The hardest part of being here has not been the language or the culture shock, although those have been pretty hard; it's been the environment. I mean the pollution, to which I was quite rudely introduced on my first visit, back in April when the biggest sandstorm of the year struck

What I'm doing now, besides breathing in excessive amounts of carbon dioxide and all sorts of other junk, writing for magazines here, especially That's Beijing, a fine and substantial English-language monthly which is essentially Beijing's answer to New York magazine (plus light censorship—unlike foreign media, this magazine is overseen in part by the government). It's through that job that I've learned a lot about Beijing and met more than a few characters, like architects, swanky club owners, environmentalists and Dashan, westerner-in-chief (check the photo below--it's not me I promise). The gig was largely thanks to Jonathan (Hollywood Reporter bureau chief) and Alexa (AP reporter), who hooked me into the large journalism scene here. I'm also covering environmental stuff for treehugger.com, which is a nice green living website. I studied Chinese for a month, but after a big spate of writing and a trip to

One wonderful and horrible feature of this country is that you can do whatever you want—as long as it doesn't include voting, protesting, looking at the BBC News website (and sometimes, my god, Google), distributing materials related to the [REDACTED] or writing news articles about natural or environmental disasters without government approval (disasters? No idea what you mean. –Ed.). What do you mean, Alex? For instance, you can get hired as an English teacher, or a "foreign expert" or a consultant or a editor or the president of a company just by showing off your English language skills or diploma from a good American school. Actually, you needn't have gone to the school, but merely mention its brand name—and if you need a diploma from that school, you can always get one printed here. You can walk around, run, or dine with your t-shirt pulled up above your belly without drawing the least bit of attention (except inside banks apparently). You can, if you're a foreigner, receive high praise for your Chinese skills from locals after poorly venturing a phrase or two in Chinese. You can stare at anything or anyone you want, though you must be ready to be stared at as well. You can (and might as well) do a crazy dance whenever you want to (or take all your clothes off onstage, as I saw a friend do recently after his punk show), because you are already always treated like a circus monkey. You can choose to eat a delicious lunch for the price of one American dollar, or you can nosh on an Alaskan black cod with baby bok choy and a cigar for the price of a used Chinese car. If you don't opt for the cod, you can speed your used Chinese car through intersections at high speed paying little heed to pedestrians or bikers, or, assuming you have not already been hit by a car while riding your nifty folding bicycle (I purchased one for half the price you'd pay in the U.S., and it was stolen at double the speed), you can ride your bike anywhere you want without wearing a helmet. If you get hit, you can get high quality care for a pile of money, or, if you're like most people in

One wonderful and horrible feature of this country is that you can do whatever you want—as long as it doesn't include voting, protesting, looking at the BBC News website (and sometimes, my god, Google), distributing materials related to the [REDACTED] or writing news articles about natural or environmental disasters without government approval (disasters? No idea what you mean. –Ed.). What do you mean, Alex? For instance, you can get hired as an English teacher, or a "foreign expert" or a consultant or a editor or the president of a company just by showing off your English language skills or diploma from a good American school. Actually, you needn't have gone to the school, but merely mention its brand name—and if you need a diploma from that school, you can always get one printed here. You can walk around, run, or dine with your t-shirt pulled up above your belly without drawing the least bit of attention (except inside banks apparently). You can, if you're a foreigner, receive high praise for your Chinese skills from locals after poorly venturing a phrase or two in Chinese. You can stare at anything or anyone you want, though you must be ready to be stared at as well. You can (and might as well) do a crazy dance whenever you want to (or take all your clothes off onstage, as I saw a friend do recently after his punk show), because you are already always treated like a circus monkey. You can choose to eat a delicious lunch for the price of one American dollar, or you can nosh on an Alaskan black cod with baby bok choy and a cigar for the price of a used Chinese car. If you don't opt for the cod, you can speed your used Chinese car through intersections at high speed paying little heed to pedestrians or bikers, or, assuming you have not already been hit by a car while riding your nifty folding bicycle (I purchased one for half the price you'd pay in the U.S., and it was stolen at double the speed), you can ride your bike anywhere you want without wearing a helmet. If you get hit, you can get high quality care for a pile of money, or, if you're like most people in

For instance: my new neighborhood—and my old neighborhood, if you count my first weeks in town when I lived with my cousins. Here we have a convenient portrait of this do-as-you-wish (but, to be fair, not laissez-faire) society. The road is Ya Bao Lu, and if you were to get knocked out somehow (and this is far from improbable on Ya Bao Lu) you might awake to think you've been kidnapped, stuffed into a shipping container and all the dust that involves, and left on some side street on the outskirts of

Here are shipping depots that are more than shipping depots, fur coat stores that are more than fur coat stores, night clubs that are more than night clubs, minivans that are more than minivans, banyas that are more than banyas, brothels that are more than brothels, and other more thans that aptly demonstrate the transformative power of capitalism. At night long-legged ladies slip in and out of the clubs and 24-hour shops and cabs, while legions of shirtless Chinese men, a good number from the country's (almost) Islamic western region, Xinjiang, emerge to pack, stuff, tape and load boxes of anonymous goods onto trucks piled dangerously to triple their height and bound for a train, new silk roads, a boat, wherever. By day, the amount of tinted glass on the cars and vans rivals that on the eyes of the many once-athletic, middle-aged Russian men and their gaudily-dressed big bleached-blonde brides, both looking like they've just come from a mafia funeral held at the gym.

The gym is probably not the one at the St. Regis hotel, located not ten minutes away by rickshaw, along with the nicest pool, in a club to which my cousins belong and to which they retire every chance they get. Next to the

Every night young Iraqi children play football in the alleys and playgrounds within the diplomatic compound in which I live. What is a diplomatic compound and why live in one? I would tell you but then I would have to bore you. To make it short, the place was an offer from Newsweek's bureau chief at a real bargain—1500 yuan down from 6000—but perhaps not when you consider it came unfurnished. However, there is, remarkably, an oven. There is also a real bathtub that says "American Standard" on it in the old cursive writing. Along with the "Norway, Land of the Vikings" mug, this place is pretty foreign—in terms of construction quality (it actually looks quite Soviet, but high Soviet), in terms of population of course, as well as in terms of what I've been used to. I last lived in a modest but still lovely apartment a few subway stops away with a great friend-of-a-friend named Claire, who's been in town off and on since high school. There we shared the traditional curiously-scented bathroom, with showerhead just above the toilet. Adorning the walls were a reprint of a soviet realism painting in which Mao is reposing in a wicker chair in the countryside and a monstrous, unironic and luminsicent photorealistic green and blue painting of a waterfall. A construction site was just across the street from us.

In fact, the whole city is under construction. The weekend I arrived, I accompanied a friend, Elizabeth, who was back in town after a three year stint here, tying up loose ends, to pick up a rug from her old house (it really tied the place together). Her old apartment happened to be inside the hutong, the traditional, low-slung, courtyard housing area that once made up the city as it spread out around the central

China's best intentions now involve building 200 cities of a million-plus people each by 2020, cooling rapid growth of 9 percent a year (but not by too much), and turning Beijing into the international cosmopole it aspires to be by the 2008 summer Olympics. That last word has of course become the mantra of possibility for everyone from officials to school children to construction workers to foreign inhabitants, some of whom, cousins included, also see the Games as a convenient moment to make the crucial "Clash" decision (should I stay or should I go?). Everything feels so provisional, so expectant, but also so uncertain. The word, looming over

Yeah, it's easy to get lost and disconnect yourself in

Some historians and urban planners can, especially the foreign ones (the same ones that are moving into the hutong perhaps). But hypocrisies aside (there are many), the urban planners have a good point to make: get rid of the past, but also discard the schizophrenia that might destroy the city. Already enormous in scale and population, already the world's dirtiest traffic jam with 1000 new cars added to its streets daily,

The bidding has stopped, the investement is slowing down (if the government can help it). But the building never seems to end. It so happened that the woman now living in

Sometimes it's exciting in a not so fun way. For instance: visa renewal. Not wanting to deal with that hassle not long ago, I planned a quick escape to

Sometimes it's exciting in a not so fun way. For instance: visa renewal. Not wanting to deal with that hassle not long ago, I planned a quick escape to  So not wanting to pay the price, and eager for the adventure, I got on a train in Genghis Khan's one-time capital and headed for the capital of his own country. It was after all the 600th anniversary of his empire, and it was a happy coincidence that three friends (Sarah, Abigail, and David, whose nom de voyage was s.a.d.) would be coming to

So not wanting to pay the price, and eager for the adventure, I got on a train in Genghis Khan's one-time capital and headed for the capital of his own country. It was after all the 600th anniversary of his empire, and it was a happy coincidence that three friends (Sarah, Abigail, and David, whose nom de voyage was s.a.d.) would be coming to

On the surface however, it is mostly a living relic not of the Mongols influence but the Russians. The most memorable building today is the gargantuan cultural center, located near the central

Of course, the Tatars and the Russians sought to undo not only that temptation but the very legacy of Khan with their own conquering in the past two centuries—the most bloody landmarks of which involved a rogue and insane Siberian baron and a deputy of Stalin who carried out an order no other Russian emissary could: to execute thousands of monks, along with their monasteries. The least populated country in the world got no help from its other neighbor, the most populous country in the world, which has been no less fierce, but perhaps more clever, with its own imperialism. The train to

Ok enough of this long march; let's have a nice long August. Please let me know where and what and when you are.

Ok enough of this long march; let's have a nice long August. Please let me know where and what and when you are.

Saturday, May 20, 2006

Notes from a distance

Sunday, April 23, 2006

My little airport

There are few symbols of globalization as epic and flashy as Hong Kong, which takes an efficiently-run system of exchange as its goal and organizing ethos, from the culture of shopping to transportation, from the shipping industry to the business-friendly regulations that have for decades made Hong Kong the world's free market city. It's no wonder so many companies set up shop here, and so many foreigners come here. Or rather, pass through on contracts of six months, a year, two years. It's a city that's comfortable, but ultimately hard to get a grasp on for a non Cantonese-speaker, considering that so much of the foreigner population is just arriving too, or on its way out, or busy with 60-hour work weeks.

I think it's telling then that one of the first things you might hear about Hong Kong, as I did, was that its airport is the world's greatest. Smartly designed by Norman Foster, he of that iconic HSBC robot-like building in Hong Kong itself, it pushes the city's cosmopolitanism and ostentation up front while taking typical international airport efficiency to unseen extremes. There is a fast mini-subway system that connects one to a whole series of terminals and escalators that ascend through airy atriums, eventually to the famous Airport Express, the fast train that whisks almost every passer-through from the airport to downtown Hong Kong in twenty minutes. From there more escalators, elevators, and another futuristic subway, the MTR, a system so punctual that when a train is late, headlines are made. Inevitably, more escalators and shiny office buildings. It's all fast, super clean, and almost completely lacking in any sense of fun.

I say "all" because it's kind of hard to tell where the airport ends and the city begins.

In March I noticed a small piece in the newspaper about aerotropoli:

An aerotropolis...is "similar to the traditional metropolis of a central city and its commuter-heavy suburbs," but "consists of an airport city core and an outlying area of business stretching along transportation corridors."

I think this describes Hong Kong pretty well--and not just because Hong Kong is organized as an Asian "hub," a place to make connecting flights, as much as it is a city. The airport extends into the city and vice-versa. As in an airport, everything feels under control, the crowds are bustling and moving via escalators and horizontal people movers, individuals rush to their next destination, or terminal, or wait in waiting areas, checking their cell phones or watching CNN, until it's time to board. Everything is easy, the drinks are expensive, the brand names are many and mixed together so you have every option, and can't go anywhere without being reminded to buy. Everything (legal) you need is available, everything is clearly marked in English, every piece of information is available. The entire construction is meant to make things comfortable or at least convenient for the traveler (check), to be attractive (check check), to be safe and efficient.

The emphasis on efficiency and security gives way to guardedness and unobtrusivity, obscuring the mechanism by which all of this works (Karl Marx where you at??). So much in an airport is unknown, hidden from view, denied, behind nylon ropes or inconspicuous doors with "Prohibited" on them. Everyone is moving somewhere, or in the logic of the airport, being moved, in keeping with airline rules and security rules and departure times. Despite the cosmopolitan feel of an airport, despite the sophistication, the overriding mode within it is a kind of naivete.

Once, when he worked in an office building, my dad was sitting at his desk late at night, alone, when two men came in wearing repairmen overalls but saying nothing of their business. When he asked them what they wanted, they ignored him, continuing to browse the office. My dad has always said he was nervous, frightened even--until they pulled their guns and asked to see the safe. All of a sudden he knew exactly what was happening. The unknown is one of the scariest things, and at the risk of exaggerating, I find an airport city like Hong Kong scary. No, in one sense it's not scary at all as long as you do what you're supposed to: go about your business and ask few questions. Follow the many rules and move along. Forget about culture, forget politics, just commute, eat, work, drink, sleep.

It's that Disney effect, a sense that something is seriously out of place beneath, generated because of, not in spite of, a facade. It doesn't matter that the facade may cover nothing at all: if you are curious about your surroundings, but living in a landscape that denies knowledge of how things work, that betrays no seams, a certain discomfort is unavoidable.

There is something especially uneasy about sliding around the shiny, Utopian, too-clean surface of Hong Kong, with the knowlege that just beyond the New Territories lies that rough giant of a superpower.

There may be nothing out of place actually, nothing missing, because maybe Hong Kong has already established by silent force, by corporate consensus if not a community culture, the model for our new global cities. This isn't meant to be critical; it's merely an observation. Just as, globalization isn't up for discussion, though how it goes down is. (O but that it's merely an observation--does that say something about late feelings of complacence here?)

There's the line in that Borges story about the library of Babel: "Every hexagon of the library was the world's exact center, its circumference was unmeasurable."

I was thinking that as the world gets smaller, my distance from the edges also seems to grow larger, to the point where those distances now feel infinite. If so many places we go and know about come to look and feel similar--ie, the world getting smaller--the more exotic and far off the other places we haven't been should come to seem. The more similar and digestible and comfortable the places we live in become, the more the other places defy imagination. Hong Kong isn't only a convenient Asian hub or airport, but as part of a globalized chain of cities, packed with ersatz culture and brand names, it's practically an argument for getting on a plane and going somewhere else.

Friday, April 07, 2006

Thai me down, loose ends

Two days ago the prime minister of Thailand announced he would be resigning. That's not why I'm in Bangkok now, though Time--where I stopped working last week--demanded my cell phone number just in case. I haven't had the pleasure of doing any reporting for them during my vacation just yet, so I thought I'd do a little now, for you. Apologies in advance: I will not be discussing Thaksin's resignation--I'm saving all that juicy stuff for a later email of course!

One thing you notice pretty soon after rolling out of a taxi from the airport--the second taxi you got in because the first one tried to rip you off--are the white people on Khao San Road (an almost inevitable destination if you're wearing a backpack), and how many of them look as if they've just checked in to drug rehab, or just escaped. It wasn't until later, in the mirror of a bright, air conditioned bootleg CD store, did I realize that the pot had called the kettle crack. My face was glistening, covered in a thin layer of dusty sweat, and it also had a beard on it. For a second my hair even looked dreadlocked. I brushed it back with a hand at the base of which sat a lotus-seed prayer bracelet (acquired at a monastery in russia but nevermind). Did I mention that at the CD store that David and I stopped in--David, my roommate from Hong Kong, is traveling with me--the one album I picked up was a collection of Pete Tong remixes? I quickly realized what was happening, returned it, steered clear of the Jack Johnson and edged towards the door. Playing on the stereo at the loudest possible volume, and still reverberating through my hot head, was Eminem's "White America."

That's not Thailand but I don't know what is yet. Some clues: as we sluggishly made our way over to Wat Po, Bangkok's big famous temple, I was approached by a man smiling a big Thai smile and trying to find out where I was heading. A word of advice: generally, when men approach you in Asia (at least in Hong Kong, but probably everywhere in the world), smiling and on the verge of saying something, try to avoid eye contact because you are probably walking into an elaborate scam. After a little shrugging and some pseudo-lingual answers, I realized he meant well. He said he was a teacher, and he wanted to know where we were heading and explained that due to a national holiday, the temples we wanted to see, along with the Grand Palace, were closed (I partly verified this later to be true--today was a celebration for Rama I, Chakri Day). Luck (that was his name) gave other recommendations and even circled them on my map just before a tuk tuk driver pulled up. The tuk tuk, basically a motorcycle with a three-person bench on the back and a canopy on top, is an apt symbol for Bangkok: strange, cheap, breezy, dirty, noisy, go anywhere you want, and just fun. Another word here: the tuk tuk, I was told, is one of the most popular instruments of scam art in the capital. Needless to say, it wasn't long before David and I were being whisked around by tuk tuk to various landmarks--the golden buddha, the black buddha, the 90 buddhas (the reclining buddha was on vacation along with, presumably, the napping boddhisatva)--while the tuk tuk driver (Luk--not Luck) waited for us outside. He even waited for us while we had lunch at a restaurant near the 90 buddhas temple (that is not the real name). During a delicious repast (like every meal we've had, esp. the street meat, not to be missed!), we befriended another wandering soul named Hillary, a medic on an oil rig in British Columbia who had come to Thailand for a few weeks on her own. There we were, finding ourselves together. It turned out her tuk tuk driver was also waiting outside, and had plans to take her to a ping pong tournament later.

I'm actually not sure that that teacher, the one I mentioned earlier, was actually a teacher. But but but everyone has been so nice--even the people who wanted nothing from us, the men who stopped me virtually everywhere we went today: the medical technician, the vagabond outside the temple, the monk at Wat Suthat. And even if each of them was a scam artist, it was my pleasure. Plus everything's so cheap, getting scammed in Bangkok (like getting some shirts made, or getting a massage) is much better than elsewhere. Something karmic to it probably.

After I ended up buying some discount tailor-made "businessman" shirts--this was the completion of the scam, I realized, but I wasn't sure who was scamming who (see, our driver gets a free gasoline coupon for every foreigner he brings to one of a handful of tailors across the city, and we thought we'd do him a favor, but the anxious burmese store owner was on to our "just browsing" game, and I needed some shirts anyway)--we paid the driver his 2 bucks and David took off for Chiang Mai, up north, where I'll go tomorrow. Tonight solo wandering took me to chinatown, a crazy fresh fish market, dark alleys full of people gnawing on things or napping, a slew of sidewalk blankets covered in the most random assortment of amulets, magazines, broken electronics, cables and used and new clothes you can imagine. Old Thai-Chinese shops selling/making things that resisted my understanding. I in turn resisted the tuk tuk drivers that would occasionally stop, especially the one that offered to give me itinerary recommendations, before asking if I wanted a "massage," or if I wanted to see a "show," or maybe go to an "open bar," or take me back to Khao San Road. I thanked him graciously for his offers, even if they weren't made out of kindness, because he was probably a nice guy trying to make money in this pretty poor country, because everyone I've met has been likable, because this is really a great city, even if I just got here, I swear on my lonely planet (er, lets go). Anyway, I found another tuk tuk, ate some roti at the muslim shop down the road and wrote this rough rough guide to you.

love you long time.

Tuesday, March 21, 2006

The Hard Sell

Not long ago, I joined my mom on a bus tour of

After a few buzzers we entered what looked like an office that had been hastily set up, about 20 years ago. Drop ceilings, florescent lights, a plaque on the wall and a cheesy display case with a bonsai tree inside. A woman ferries us into the factory, where a dozen smart looking people are assembling knockoff jewelry. One booth where men are preparing the liquid metal for the castings, a floor of ten men polishing stones and assembling the jewelry, another booth where two technicians are working on the more delicate pieces. We look at a huge piece of jade attached to the wall. And then she takes us into the showroom. A clean, shiny, carpeted huge room, like the incongruous stores you end up in after a tour through the dark halls of the museum. Six of us, and behind about twenty display cases, a silent army of twenty salespeople, dressed in what I now remember as tuxedos. They were all staring at us, slight smiles. We were outnumbered. It was a hard sell David Lynch has probably imagined.

One woman tried to sell me the same ring my mother was looking at, even though I told her I don't really wear them. After she tried to sell me a silver dog pendant. Before she tried to sell me a bracelet, before I told her I actually don't wear any jewelry. Before she pointed at the wooden/lotus seed bracelet I got at a monastery in Ulan Ude and insisted upon a jade one to match. Before I hid in the corner.

Anyway, it didn't occur to me until later a) that probably every hapless city tour goes through a place like that and b) how apt a symbol of Hong Kong as anything a place like that, where we were, was. The small factory (factory should be in quotes) was merely the spectacular anteroom to the showroom, the magical attraction--like an alchemist's workshop--that not only justifies the subsequent shopping detour, but turns the shopping experience from a detour into a logical part of the tour. This isn’t a cheap ploy to insert some souvenir commercialism into a city tour, but a great opportunity to get up close and personal with the city itself, like a trip to the Peak, or to the Jumbo floating restaurant, or a ride on a sampan, or a stop at

This is apparently what

Another symbol, albeit exaggerated, of

(Beneath a good portion of the world's smog, you can just make out the People's Republic of China)

Anyway. That factory wasn’t really a factory. It was another part of the showroom.

Last Sunday, David and Yumi and Austin and Hanna and I rode the commuter KCR train for an hour to Lo Wu and made our way over there, to the city of

Like the DVDs, nothing there seemed real. The mirror-covered mall sitting adjacent to the train station reminded me of a space ship-I thought of the now doomed Kurfurstendamm in

J’s driver picked us up in a van from the hotel in Shenzhen. There was a yellow Lamborghini parked outside. We drove fifty minutes on highways that were still under construction. A patchwork of fields and hills and anonymous towns and apartment complexes raced past the windows. For a moment it was as if we were driving along some proto-strip mall and freeway town in an isolated part of New Jersey that had just been discovered and was rapidly being brought up to speed with the rest of the suburban state; China seemed, in this early impression, to tell an alternate, faster story of development, American economic growth on speed. (For a sense of the pace at which development moves in

If today is typical, builders will lay 137,000 square metres of new floor space for residential blocks, shopping centres and factories. The economy will grow by 99 million yuan (£7m). There will be 568 deaths, 813 births and the arrival of 1,370 people from the countryside...

It’s worth noting that this is also at the head of the vast new 600km long lake created by the Three Gorges Dam project; the refugees from the flooded land have helped swell the city's population. For an idea of development and that dam, check out Edward Burtynsky’s photos; thanks ross)

Soon we were patrolling dusty sidestreets until we stopped in front of an unassuming white tile four-story house. The driver tapped something on the keypad and we were soon inside the dining room watching a Korean soap opera on satellite.

The first sign that J’s job was serious came when we walked past the guards at the entrance to the factory. Three men in uniform saluted him. He nodded, he had gotten used to this.

Once on a field trip in elementary school, I was inside a potato chip factory in

All told there were 4,000 workers in four factory buildings. Another factory was being built next door. Aside from the enormous rooms with people working robotically, sometimes in front of open flames, for eight hours straight (the white board in J’s office evidenced attempts to adjust the shifts so as to fit two into a day while staying within legal limits), I was surprised by the sheer amount of jewelry they were making. It was all cheap copies—costume jewelry—made of glass and metal with a special coating to make it look real, and probably will sell for 15 times its cost of production ($1) at stores in Asia,

We ate lunch at his townhouse, a great Korean spread prepared by his cook, who once worked in a Korean restaurant. We talked about surfing, about the market for surfboards, which J is planning on manufacturing (secret!). Then we played some Korean billiards upstairs in the “game room” on the roof. The angles are so important, in Korean billiards. There are no pockets. We talked about relationships. A person watched us from the adjacent roof. Smoke in the background. Yes it was surreal.

We piled in the van and headed into town to get some DVDs. This is one of J’s favorite pastimes. Fortunately, his driver speaks Mandarin, which is useful if you want to get past the standard selection out front and dive into the real stashes, hidden from the sight of inspectors who’ve been making raids in recent years, holding bonfire parties in the streets in the name of the MPAA. A trip to another store, and upstairs into a large crawl space, a secret room that almost defied the laws of architecture, behind a fake bookshelf, revealed an embarrassment of movies. Imagine raiding Quentin Tarantino’s tomb. In the dust light, in the middle of the piles of shiny boxes was the shiniest, the jewel in the crown that I had been searching low and low for, that had escaped me online, in Chinatowns, even at Moscow's DVD mecca, the electronics market at Gorbushka: The Complete X-files. Imagine: the cancer man episode, the freaks episode, the one written by William Gibson about a killer artificial intelligence that lives inside a trailer, the alien rock, the episode that takes place in the 80s when Mulder carries around that enormous cell phone, etc. I make no apologies for this.

But I couldn’t do it. It wasn't guilt. For all I knew 20th century fox had changed their name to 20th century, as the box indicated, and had begun to sell the entire series on DVD for 10 USD (Though Chinese bootlegs are packaged quite convincingly, occasionally you'll come across the description for a completely different movie, or film reviewer quotes apparently chosen by a non-English speaker, like the unfortunate "Flawed!" I spotted on the side of a Bruce Willis movie.) No, the box was just too big. I opted instead for a handful of recent classics like Crash (pretty, pretty didactic) and Jia Zhangke’s The World and Good Night and Good Luck and Walk the Line (I haven’t seen them yet). We left giddily with about 30 discs total for about 30 dollars.

I stepped outside as J’s driver was haggling with the guys behind the counter and for the first time glimpsed a bustling Chinese town that showed almost no sign of foreign influence, no sign in English. I looked into cell phone stores, and into tea shops with women standing outside in uniform waiting for their afternoon customers, and watched an endless chain of men ride past carrying large bags on the backs of their bicycles, or other men. Of course there was a touch of the foreign beneath. I got the sense that in some way, all of this had been underwritten by large companies with home offices in

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

Pasteboard masks

I’ve been meaning to write something somewhat meaningful about this city, something to distill things down in a way that will clear my cellared head and show something for two month’s of work/party zombie life. The Art Walk through the galleries of

The idea, au currant in a number of cities, is to plot on a map a group of galleries in a given area, reserve one night for those galleries to open their doors and put out some wine and cheese for caravans of people in suits who choose to see their art and be seen too. I’m not sure how it works elsewhere but in

The high ticket price, I was told, was because this was a charity event—but I could see no mentions of the charities.

I had passes, courtesy of a friend who couldn’t go, but the whole premise of paying to play made me feel yucky. I didn’t want to be conspicuous as I crept around, stealing glances at art, stealing samosas, stealing down the street to the next unsuspecting den of red-wine antiquity or pomo iniquity, and besides, I figured it would be fun, funny, a little provocation on a night of preening and peering to wear a wig. It was a remnant from my suzie wong costume—the qipao/lipstick/wig getup that almost won me best costume at the corporate dinner the week before, had not I been robbed by a well-meaning but boringly-dressed hooligans from HR pretending to be the Partridge family. Please. I was also robbed of the “best karaoke” performance by some HR vixen. In a way, the wig on Art Night was my form of revenge on the system.

It didn’t really work in the bright lights of the galleries—or maybe, just maybe, it worked too well. People were taken aback by the discrepancy between the wig (black) and the eyebrows (brown); and yet, I’m not sure they could tell what they were seeing. They just knew something was out of wack. So they stared, standing right in front of me, standing across the room, etc. Sipping their red wine, they couldn’t quite figure it out. A sweater, wrinkled pants, no tie. A black mop. I had become a work of art, surrealist global sculpture, a non-corporate piece des resistance, inexplicable cocktail conversation starter. I’m embellishing a bit, but stay with me.

Just how unrecognizable was I? Let me tell you. As I only had myself as date—and what a beautiful date she was, those black curls, those rosy cheeks!—I knew I would bestow the extra ticket on a lucky feller or lady. It just so happened that as I was registering—only in Hong Kong would you have to register to do this art walk thing—a man in a suit and an upper-crust amused, British voice slid up beside me with his 400 dollars in hand. Quick, Alex (no, I didn’t adopt another name for the evening)—that ticket’s going to waste! Don’t let 400 dollars also go to waste! I said something, stretched out my hand and handed it over.

Only later—after I had run into him a third time at a gallery, as he was talking to an owner about actually buying something—did I realize that a) this was the last person who needed a free ticket and b) I had had dim sum with this man a few weeks earlier. In fact, he had given me and David and a random Dutch man a ride on his boat to get to the dim sum place. He is David’s “uncle,” and is one of the few people I’ve ever met who can claim that rarefied title “shipping magnate.”

When I tried to start a conversation, the second time, he made it clear, albeit politely, that he wanted little to do with me. Not only did the wig make me a stranger to him, it made me kind of freakish. Remember: brown eyebrows, black hair. Also, brown sideburns. OMG, can you imagine anything weirder or more freakish??!

Of course the woman who registered me had recognized me almost immediately. She’s married to the owner of the coolest gallery in town, Para/Site. So had my cousin’s friend, Cameron. Same with Elizabeth, a friend of a friend I had met over a month ago. As I stood talking to her, Alexis strolled up—he is merely a budding “shipping magnate” who had been at our party—and he recognized me too. They were all apparently a little weirded out, probably as much by the wig as by my eventual explanation: I wanted to try to be anonymous. Ha! Not in

Just not yet.

We ended up going to a gallery—right across the street from my apartment, incidentally— where the owner told me that he preferred if people disliked his art. That way, the art would stay more pure, higher. And presumably, with less people visiting the gallery, there would be more wine for him. (I should say that overall the stuff these galleries had to offer with notable exceptions -- largely contemporary painting -- wasn't so bad.)

Later, we went to some clubs. We crashed a party for some avant gallery at a rooftop club, and ate free steak. A slovenly, drunken American woman came up and said, “Gawd! I hope that’s a wig!!” I told her it wasn’t and buried my head in the mirror tabletop, but hadn’t had enough to drink yet to bring myself to cry.

We ended up at Dragon-I, that fussy melting-pot of models and bankers we visited in the early days of being mild. In a moment of indiscretion and abandon, the wig came off—I forget how—and before the night was over, it had adorned Sarah’s, Elizabeth’s, Alexis’s and a few other people’s heads. Need I say more?

It was a lot of fun—the Dj’s selection was surprisingly smart and fun, and the models didn’t get in the way too much. The pals were pretty awesome too.

But could this be

I guess they didn’t exactly feel invited to Dragon-I, which has a scrupulous door policy. Ditto with the Art Walk, with its high admission price, location in the white-bread, appropriately named

Thing about Hong Kong is—and I’m trying to imagine another city like this—is that it’s premised on a somewhat comfortable economic (and racial) separation. The colonial legacy is strong, no doubt about it, but the city’s half-century emphasis on capital, convenience, and consumption—which may be the most popular characteristics of first-world money making—has made this an especially easy place to seclude oneself from the less comfortable parts of the world. That is to say, foreignness, poverty, the means of production.

Nevermind the irony about communism and capitalism. How ironic or appropriate is it that the capitalist world’s favorite point of entry to Marxist China is a place that conceals the intricacies of the situation, that feels as far away from

In a sense too, in the context of globalization, Hong Kong might be as close to

So easy to get the sense these days, in a hallway or a hotel or office or street or paved road covered in cabs and busses, that we could be anywhere. (Aside: can we be anyone?)

But

It’s the same discomfort one might feel upon returning for the seventh time to Disneyworld—a sense that there is something behind the façade, there’s something that’s making all of this wonder possible, something that has to give somewhere so we can get, but that every force is conspiring to prevent you from uncovering it. The censorship of the future, liberal capitalist style. Every time you try to get behind the façade, it shifts, so you’re always on the outside. Try to stab through it and you hit a great wall.

(The eagerness to live inside the walls was symbolized, in absurd, exaggerated style, last month at the ground zero of first world fantasies. When Disneyland Hong Kong oversold tickets one day, hundreds of ticket-holding Chinese families who had saved up to come from the mainland were left locked outside. So they began pushing their children over the fence, like refugees from a harsh reality.)

The Ahabian madness that might set in temporarily in the upper regions of Hong Kong is quickly calmed by the gentle reminder that, sure this is part of China, but you’re living comfortably (SoHo etc.) and hey, why not come back and have a beer with the models?

The massive sense of façade—that you reside in some capitalist amusement park, or in a super mall—is only heightened by the fact that life here seems so oriented to buying things. People spend their weekends at shops, shops line every metro station, you can’t throw a dumpling without hitting a mall.

And where does all the cash that runs this shopping machine come from? That too is hidden, in a way that exemplifies, that defines, the

For the reverse, “dialectic image” of this, see the crowds of young Filipino live-in maids who gather beneath these buildings every Sunday, huddling together over card games where there is no money to be gambled. Gentleman’s bets. And the hostess bars in Wan Chai.

Another good symbol is the surgical mask.